So, ‘that’s a wrap”, as I believe they say in the film industry. This is the final post in my Painting with light series, but before I sign off, here are some advanced tips and tricks to make your Painting with light stand out from the crowd:

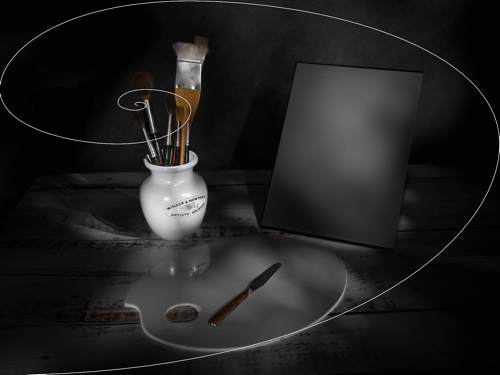

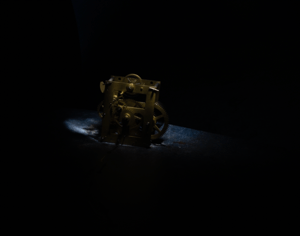

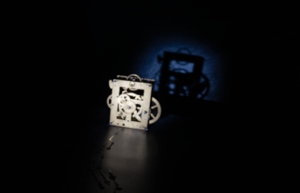

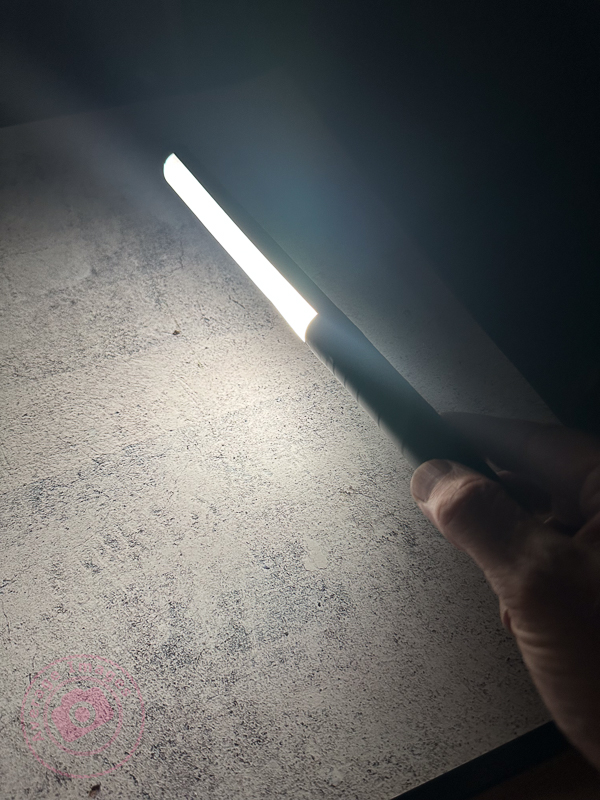

- Don’t just shine your torch whilst standing behind your camera; the image will look flat and 2-dimensional. Move to the sides and paint the light from there. This will bring out shadows and texture to give the image depth.

- Don’t paint the light from the same height every time. Stoop down or hold the torch above your head to vary the direction of the light beam. This will also give depth to the image.

- Move the beam of light in strokes (a bit like a paintbrush) – slow, overlapping strokes to create brighter areas, and faster, sparser strokes for duller ones. The image will be far more interesting with varying intensities of light.

- Keep the light moving at all times to reduce the chance of hot spots.

- Remember that different surfaces react differently to the light; dark, rough surfaces require more lighting than pale, smooth ones.

- Unless you are standing directly behind something solid, don’t point the torch back towards the camera otherwise you will create flare (or use a modifier).

- Try to include some ambient light into outdoor images, maybe the faint glow of the sky, moonlight or stars.

- Used coloured gels to create interesting variations in the lighting of your image.

And some post-processing tips:

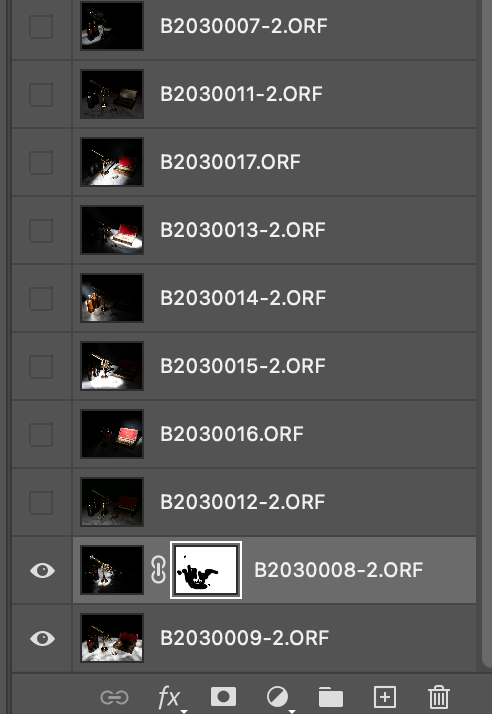

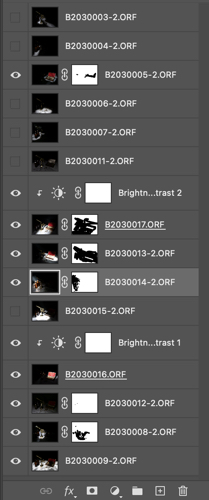

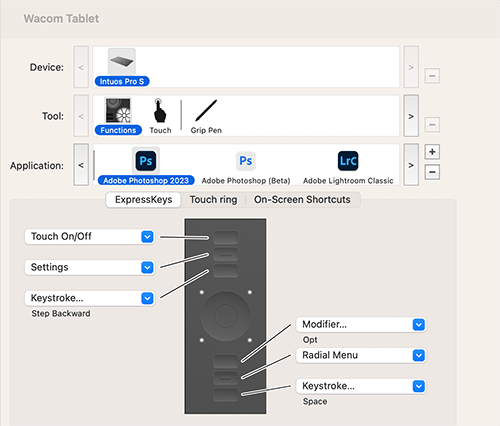

- Take many shots of small areas of the scene to create multiple layers – you can then adjust each one individually to create a detailed final image.

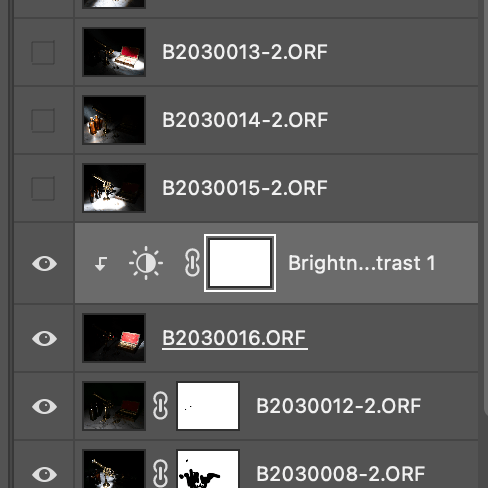

- Create a layer mask for each layer and paint out everything other than the torch-lit area. This gives you full control of each element of the final image.

- Vary the opacity to reduce the brightness of each layer to change how imposing they are in the final image.

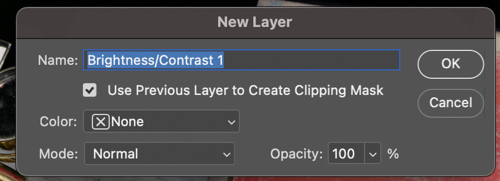

- Create an individual adjustment layer for specific layers so that you can change the exposure, contrast, light balance and even colour.

- Keep your monitor clean. When working with very dark images, every smear or speck of dust shows up – and I’ve lost track of how many times I’ve tried to remove a blemish using Photoshop only to find out it’s actually on my monitor!

You can keep up-to-date with all of my blog posts by subscribing for free to receive updates via your email inbox or the Reader app: