A Painting with light is composed of two separate compositional elements; the physical composition and the lighting composition.

The physical composition is the scene in front of you and, like any photography, there needs to be a subject and the same artistic ‘rules’ apply: leading lines, rule of thirds, etc.

I suggest that the best way to achieve a good physical composition in Painting with light is to take a test shot in the light so that you can see the elements within the frame and decide which needs to be lit later on. You can also miss some distractions in the darkness, which may spoil the composition but are only noticeable when you view the image on a large monitor.

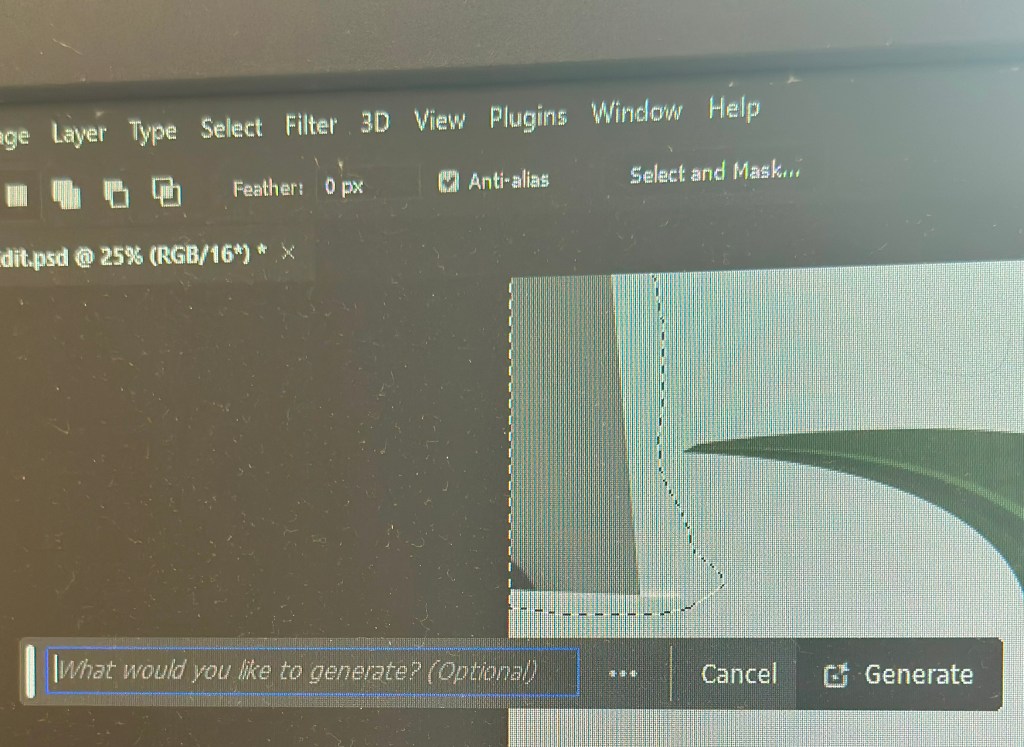

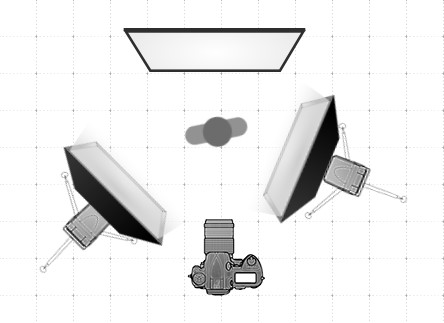

The lighting composition is what you are going to add to the physical composition. In most other genres of photography, you are ‘seizing the moment’, but in Painting with light you are ‘creating the moment’. You need, therefore, to be able to visualise how the scene will look and how to use the physical elements in the scene to optimise that visualisation. This is not particularly one of my strong points, which is why I prefer to take multiple shots and then combine them together in post-processing. In this way, I can change the emphasis of individual elements as I build up the overall lighting composition. We will look at post-processing in later blog posts.

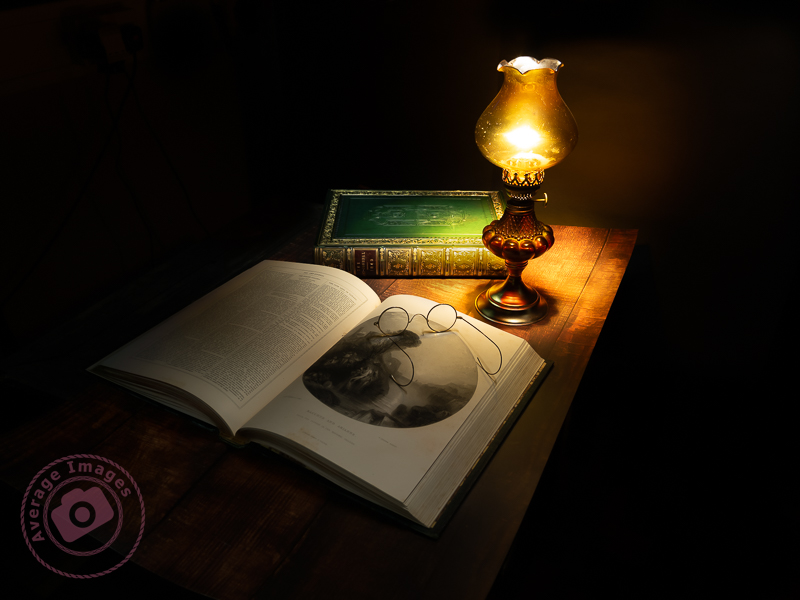

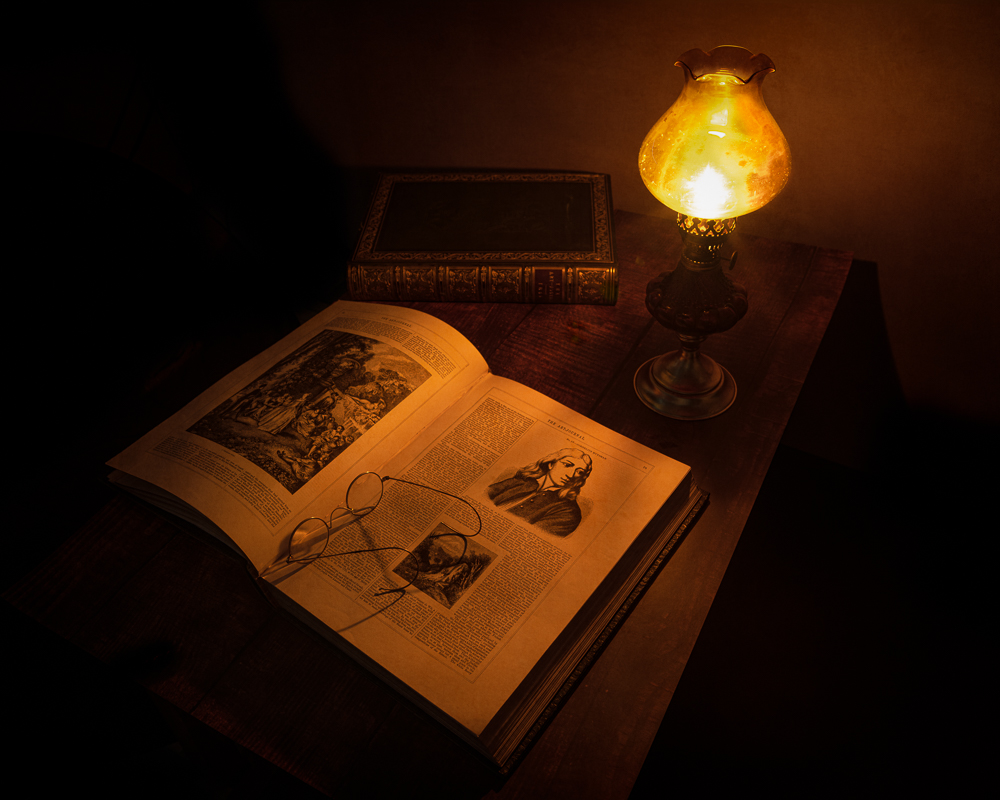

“The hero and the supporting cast“

This mantra is often used by still life and product photographers and uses the analogy of a theatre play or a movie that usually has a hero (or heroine) who is surrounded by others who give context to the situation (the supporting cast). Although the hero may be the centre of attention, they would be meaningless without the supporting cast. Neither is more important than the other.

And this is never more true than with Painting with light. There needs to be a subject (the hero) and then other elements within the shot, and the way that you light them, become the supporting cast.

An advantage of producing the final image as a composite of multiple shots is that you can vary the contribution of each of the ‘supporting cast’ so that a balanced image is created. The ‘hero’ will still be the main subject, but in a subtle manner, whilst each of the ‘supporting cast’ will have their own place as secondary interest in their own right.

Whether your composition works to create a great image is always a gamble; sometimes it will work, and sometimes it won’t, but don’t leave it to chance and put as much thought into it as possible.

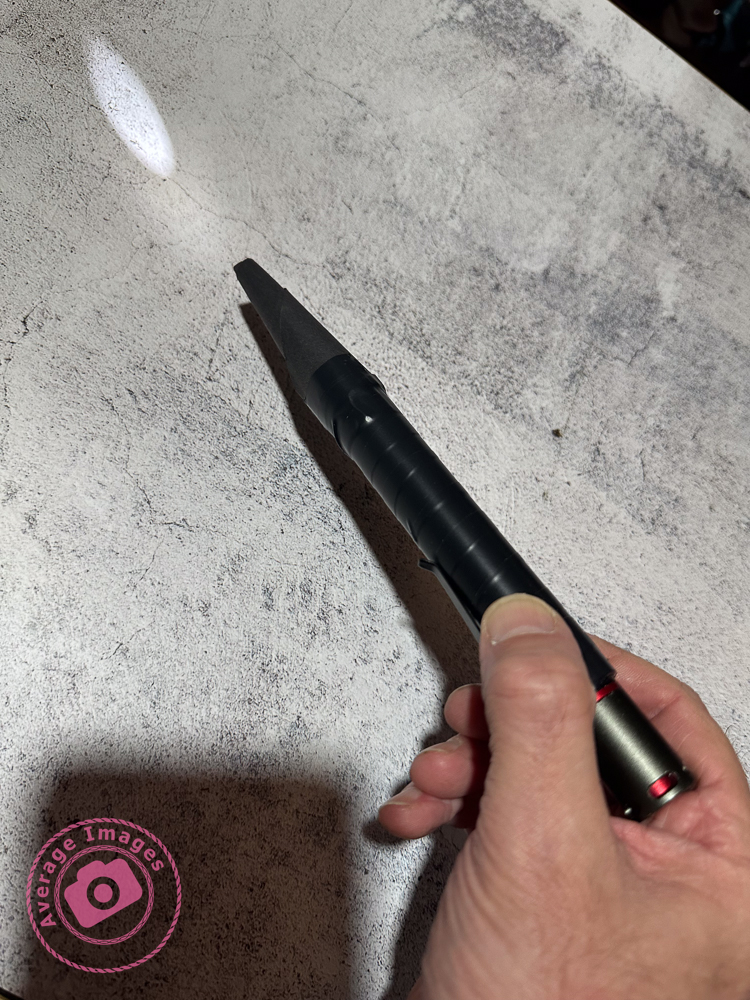

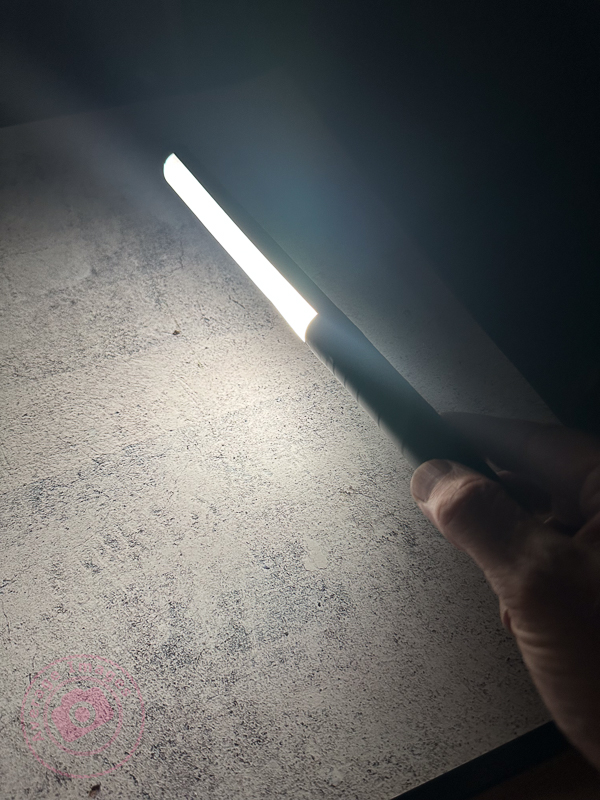

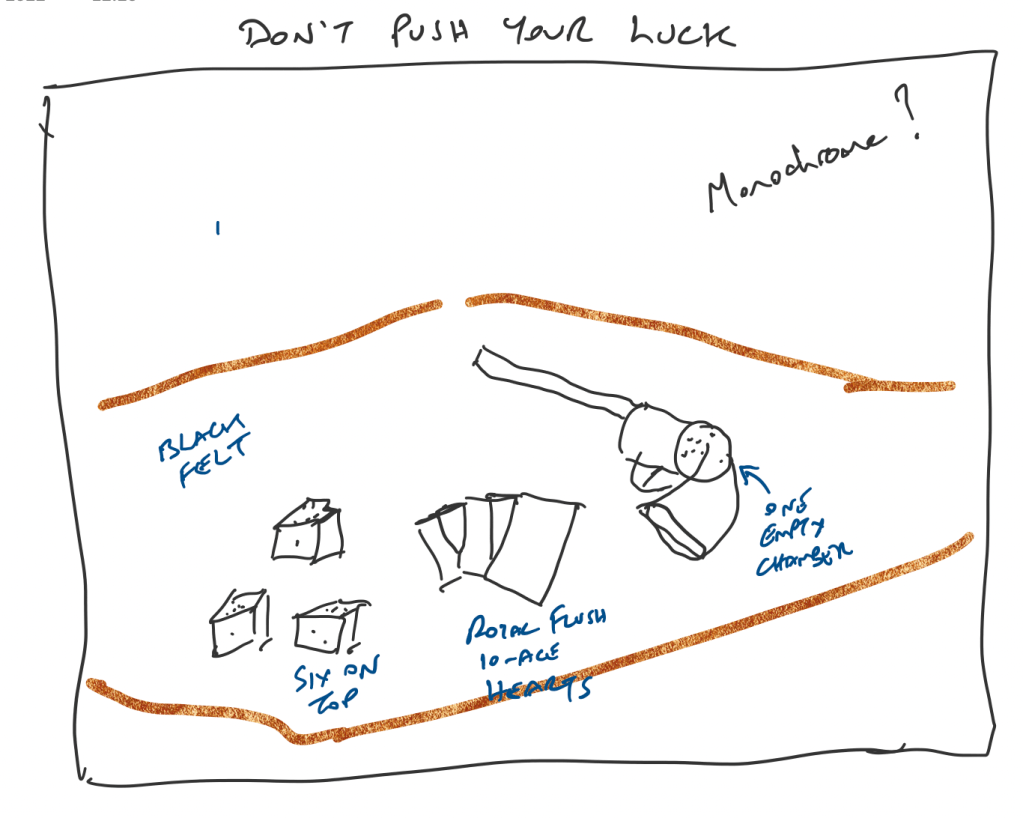

This leads me nicely to my featured shot: “Don’t push your luck“. I find it useful to pre-plan compositions whenever I can and use Microsoft OneNote as a sketch pad, using my iPad and Apple Pencil. The ‘gun’ is actually a starting pistol (and totally harmless), and I purchased the dice and cards specifically for the shot. You can see that my original plan was to create a monochrome shot but, during post-processing, I decided that it worked better in colour.

The title of this post comes from the lyrics of the song ‘Light My Fire’, written and performed by the American rock band The Doors in the 1960s. There have been numerous cover versions since then, with Will Young’s release in 2002 being one of the most successful.

Remember, you can keep up-to-date with all of the Painting with light blog posts by subscribing: