Coalport. The clue is in the name – it was a ‘port for coal’. It didn’t evolve naturally, like most towns and villages, it was the brainchild of William Reynolds, a local iron master, who, in the late 1790’s, wanted to create a transhipment interchange to transfer coal from barges, brought down from the Shropshire coalfields, onto river boats, so that they could take it downstream to Bristol and the world beyond.

To make this work, he needed people – and so he built a town to house them. It was a ‘New Town’, ironically now located within the ‘New Town’ of Telford.

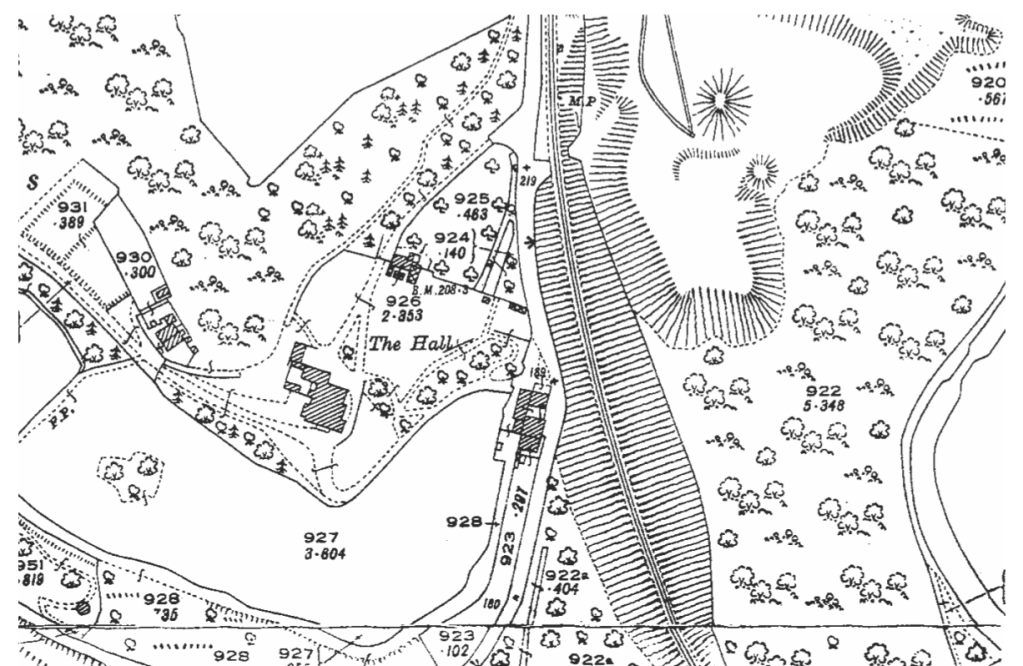

The coal was transferred by canal barge on the Shropshire Canal to Blists Hill and then down the Hay incline plane onto another section of the Shropshire Canal dug parallel to the River Severn. This lower section of the canal actually ran for about a half-mile and was served by warehouses, wharves, quays, and cranes to allow the transfer of coal from the barges to the river boats (called Sprys) and, of course, goods being transferred in the opposite direction.

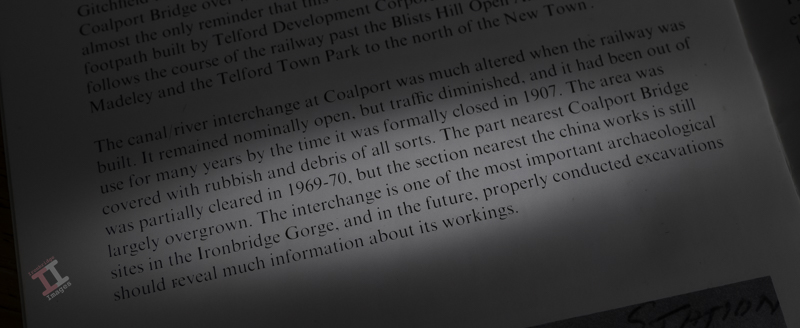

The transhipment interchange finally closed in 1907, its demise partly accelerated by the arrival of the LNWR railway line (see Secret Ironbridge: London and North Western railway), and went into disrepair. In 1978, the Ironbridge Gorge Museum Trust published a booklet “Coalport New Town of the 1790’s” and stated, on page 10 “The interchange is one of the most important archeological sites in the Ironbridge Gorge….“.

Sadly, the lure of profit led the Trust to sell the land for housing, and modern townhouses now cover the site.

A short part of the Shropshire Canal has been restored, from the bottom of the incline plane to the Coalport China Works. A small iron footbridge crosses the canal, although this is not original to the site. Further on, the line of the canal has been (sort of) marked with coloured tarmac on the road through the modern houses.

At one time you could still walk down the entire length of the old canal, but the inhabitants of these modern houses (now called Reynolds Wharf) have had the footpath closed off with a locked gate to create their own private enclave. It’s ironic that the area that led to the creation of the village is now out-of-bounds to the majority that live there.

Once past the housing, the distinct indentation of the canal can still be seen in the undergrowth, almost up to another iron bridge, which crosses the river at the eastern end of Coalport village.