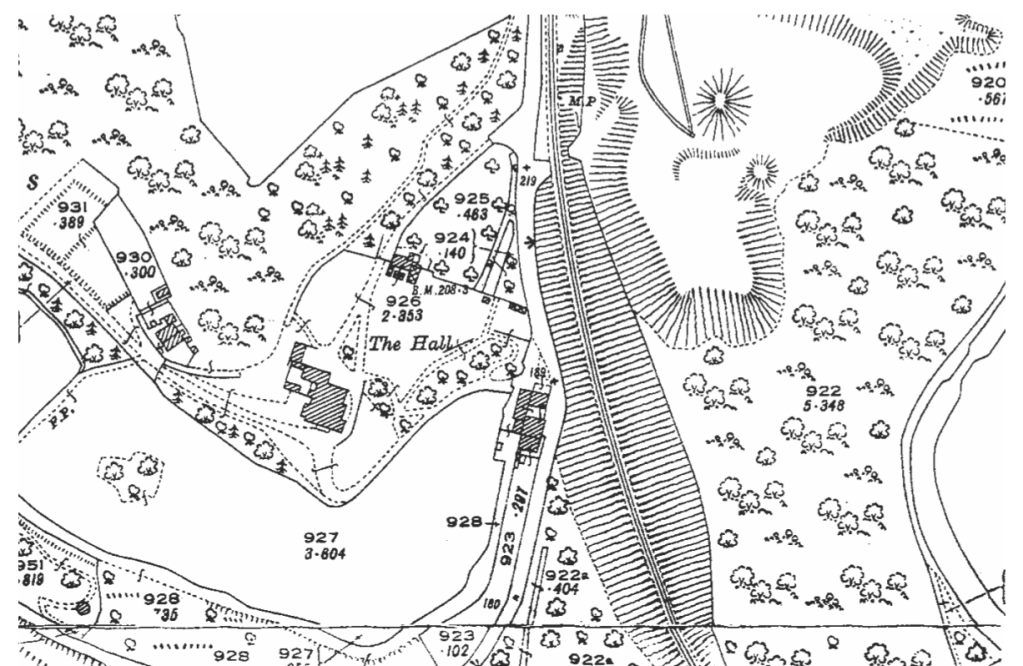

If you travel into the Ironbridge Gorge from the town of Madeley, you will pass down a road called Legges Way, named after George Legge, who owned the Blists Hill brickworks from 1912 to 1938.

Although it may not be immediately apparent, the first part of this road is actually laid over the bed of the London & North Western Railway (LNWR), one of three railway lines that once ran into the Ironbridge Gorge. This branch left the main Wellington to Stafford line and ran down to Coalport (East) station and its terminus.

After travelling down Legges Way for less than a half-mile, you will see two bridges crossing the road. The much taller one is called the Lee Dingle Bridge, built in the 1860s with impressive, tall, blue abutments carrying a lattice-girder frame. It was designed to carry a tramway, carrying coal from the nearby Meadow Pit colliery to the Blists Hill ironworks. Initially, it was painted cream, then blue, and it was much later in the 1960s when it was overpainted with its current grey colour. The smaller one was built as a footbridge when the railway was built, probably to allow workers to reach the Blists Hill ironworks and brickworks from Madeley town.

Just after these two bridges, the line of the railway drifts off the roadway to the left. Fortunately, you can still follow this because it is a footpath known as the Silkin Way, which leads you to a short tunnel which supports the main entrance to the old Blists Hill Ironworks.

At first glance, you may think this is just not high enough for a steam train to pass under – and you would be correct. In the 1960s, a huge double-pipeline was installed to take the storm water from the southern end of the newly developing New Town of Telford. Rather than dig a trench, they just laid the pipeline on top of the old railway track bed and covered it over. Hence, the pathway is much higher than the original railway track.

A little way after the tunnel, some metal fencing denotes the point at which the pipeline leaves the old railway line and continues downwards through the trees to the outflow into the River Severn. The pathway then reverts to the original level of the railway line.

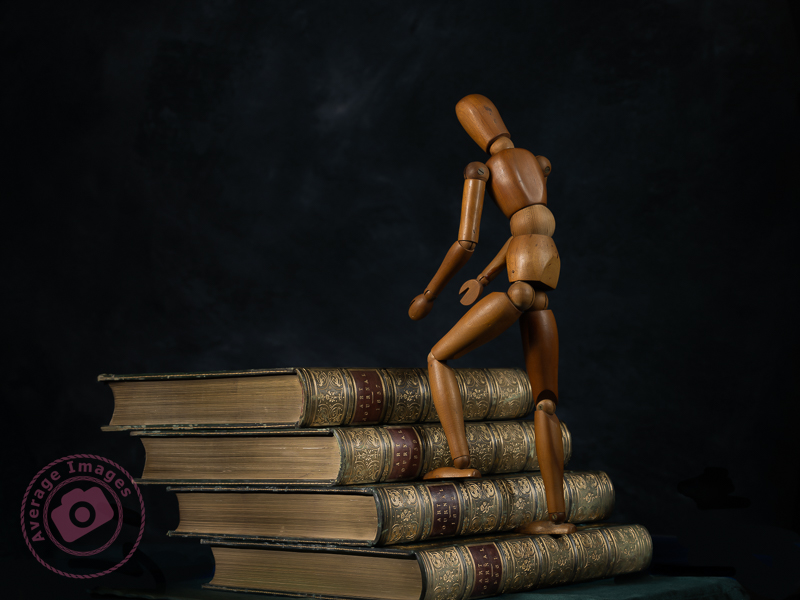

Further on, you pass under a much more interesting bridge. Built in around 1860, it supports the Hay Incline Plane – built some 70 years previously to transfer flat-bottomed iron tub boats down the steep valley side from the upper section of the Shropshire Canal in Madeley to the riverside section of the same canal in Coalport.

The bridge is unusual because bridges are usually flat on top to take paths, roads, and railways, but this one was designed to support an incline plane, so the top is distinctly angled. It is also a ‘skew’ bridge – in that the arch runs at an oblique angle to the spandrels that support it. At first, this may seem unimportant – until you think about the complexity of the brickwork and that it was built over 160 years ago before any computer-aided design. These types of skew bridges became increasingly necessary in the nineteenth century as the railway networks expanded and had to cross existing roads and canals without disrupting them too much.

The railway line then starts to level out and run parallel to the river and eventually passes under yet another bridge, which, unusually for the Ironbridge Gorge, has stone parapets rather than brick ones. This road crossing is only single-file and crosses at a sharp angle – meaning it is ‘blind’ to drivers in either direction (reversing often ensues). Beneath, a retaining brick wall has failed due to constant subsidence, letting the soil spill down – and now a large sewerage pipe takes up some of the space. It’s hardly believable that once this bridge was wide enough to accommodate two railway tracks (although only one ever went beneath, the second terminating just before).

Not much further is another road bridge, which signifies the terminus of this LNWR line. It originally had cast iron riveted sides, but these were removed and replaced with brick in the late 1980s. The platform of Coalport Station (East) was situated underneath this bridge – although all signs of this have now long gone, and adjoining this was a railway yard, built in the 1860s, which was surprisingly lavish, with a large engine shed, a palatial double carriage shed, a goods shed, a water tower and, initially, an engine turntable. It survived for 100 years until the line was eventually closed in 1960.

It’s easy to get nostalgic and have a vision of a small steam train chugging through the trees overlooking the river in the sunshine – but the reality was that this was an industrial area, dominated by chimneys belching out black smoke from the furnaces that powered the Industrial Revolution, operated by workers who lived in quite squalid conditions. It certainly wasn’t somewhere to come on your holidays.

Railways declined throughout the UK in the 1960’s due to the rise of cheaper and more flexible road haulage. Even the small village of Coalport had its own haulage company. More of that in the next blog post of this series.

If you want to see more about Secret Ironbridge, subscribe to this blog (for free!) to keep up-to-date via your email inbox or the Reader app