In 1898 the local newspaper carried a report of a nasty accident that occurred to a young girl on a bicycle in Jackfield:

On Saturday Miss Milly Pritchard of Ellsmere met with a serious accident. It appears that Miss Pritchard (who was on a visit at Mrs Doughty’s, Tuckies House) went for a bicycle ride with Miss Doughty, proceeding from the Tuckies House down the road leading from the Dingle to the Severn. From some cause or another Miss Pritchard lost control of the machine, which travelled at great speed, passing under the railway arch, and then swerved around and with great force came in contact with Mr Charles Perks’s garden wall. The unfortunate rider sustained a compound fracture of the jaw, also a compound fracture of the left knee, and the machine was smashed. Mr and Mrs Perks carried Miss Pritchard into their house and placed her upon the sofa, after which Miss Thompson (district nurse) and Mr George Bunnager (member of St. John Ambulance Association) rendered first aid. Dr. Collins of Broseley was sent for, and under his care Miss Pritchard is progressing as favourably as can be expected.

Wellington Journal, 30th April 1898

It doesn’t say how old the girl was, or what the after-effects of the accident were – although with compound fractures of both the jaw and the knee it can be assumed that it was a lengthy recovery. This was 50 years before the founding of the National Health Service in the UK which perhaps explains why the poor girl wasn’t taken to a hospital – because they were only available to the wealthy.

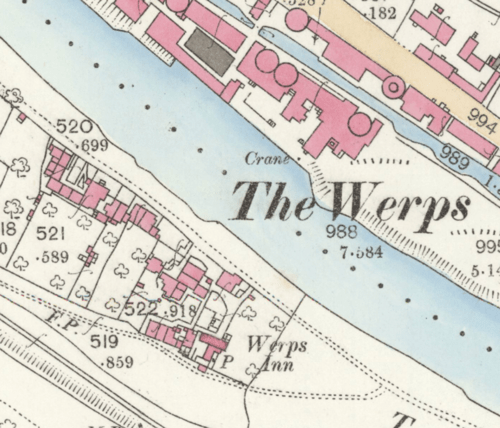

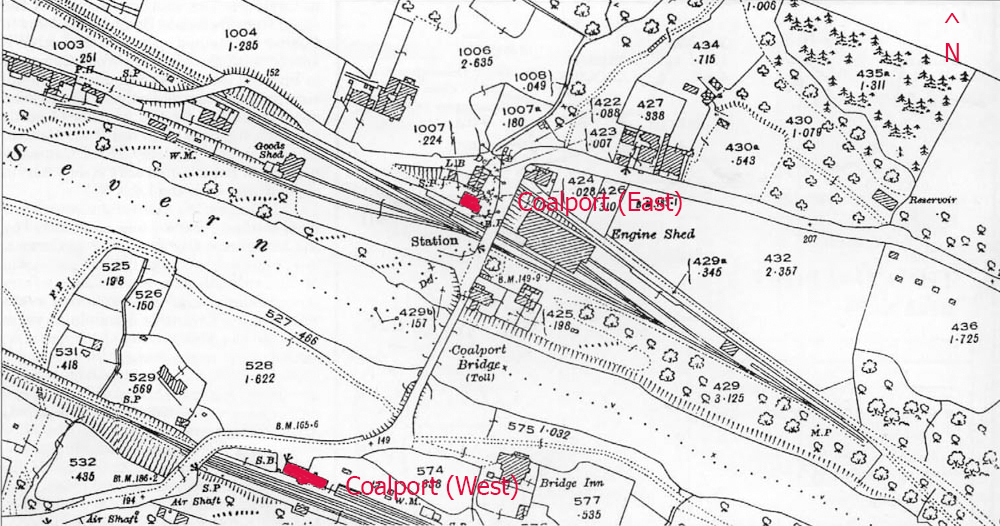

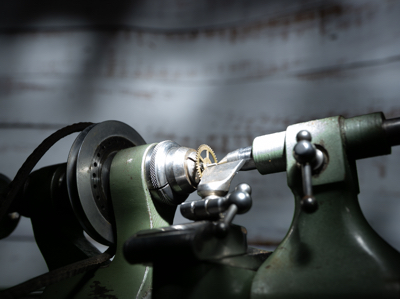

Here is the view that Milly must have seen as she careered down the lane, under the railway bridge carrying the Great Western Railway, and onwards into the wall beyond:

In reality the scene is littered with street furniture: height restriction signs, a salt bin, various random signposts and some plastic bollards leaning at odd angles. I removed them all in post-processing to recreate the picture as it would have looked at the time.

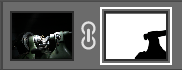

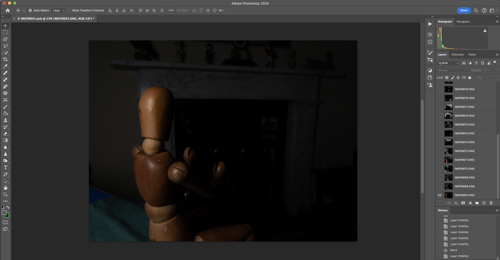

I had an idea to add “a Victorian girl on a bicycle” to one of the images using the ‘Generative Fill’ function of Photoshop, which uses Artificial Intelligence (AI) in order to create elements within an existing image. Here are the suggestions it gave me:

Those of you who think that photography is dead because of artificial intelligence, clearly don’t need to worry just yet!

Milly may have survived the accident, but there was worst to come. Just 16 years later, the Great War (World War One) broke out which, as we know, was a brutal period in our history. Many died, including those from this small community, and a unique memorial was created in their honour. More of this in the next Secret Ironbridge blog post.